Large populations near the sea are vulnerable to coastal floods, making coastal safety and sustainability an urgent societal priority. This is especially true in the Netherlands, where over a quarter of the country lies below sea level, and the main protection from deadly coastal floods is a barrier of wide, high sandy beaches and dunes. However, this sandy buffer is constantly moving and chronically eroding. To plan effective future coastal adaptations, we need to know where that sand is coming from, going to, and which paths it takes to get there. I am delighted to share that I have just received a Veni grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) to investigate this!

Where is the sand on beaches going, and how does it get there?

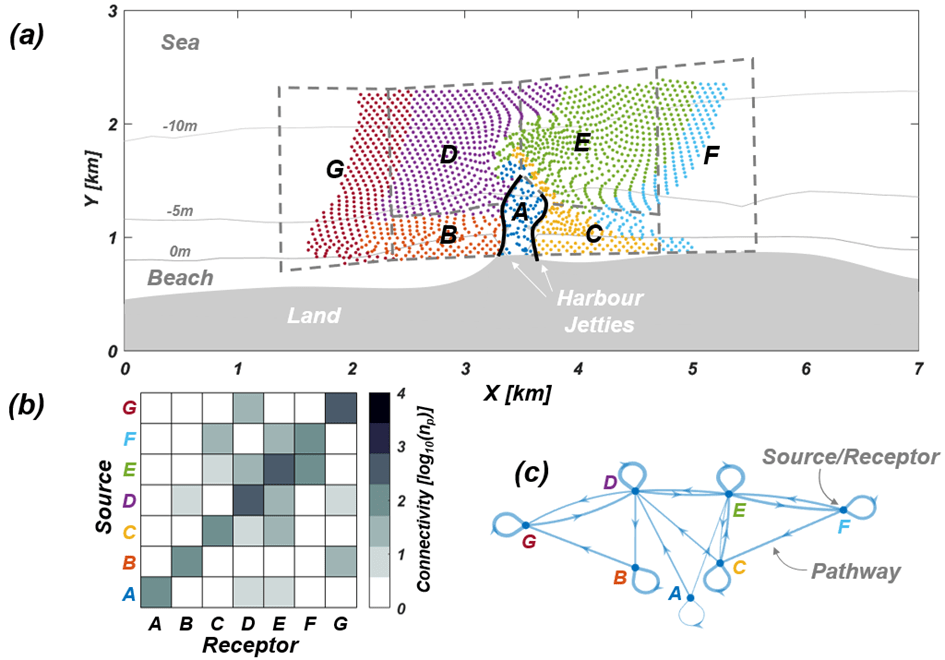

My overarching goal is to enable effective sediment-based climate adaptation strategies for vulnerable coasts. To approach this, I consider coasts as an interconnected network of sediment pathways, like a subway map showing how stations are linked. This connectivity reveals the hidden structure underlying chaotic sediment pathways through coastal systems. These pathways are immensely difficult to identify on real coasts due to the challenge of tracking individual sand grains from multiple sources in such a dynamic environment.

Proof-of-concept connectivity analysis of a beach and harbour.

(a) Map of tracer particles in example SedTRAILS model from 7 different source patches at a snapshot in time. (b) The number of particles (np) from a given source in each receptor is counted to yield a connectivity matrix, graphically represented by a connectivity network diagram (c).

To deal with this challenge, this grant will enable me to develop both a scale model in a physical laboratory and a numerical model in a digital laboratory. In a wave tank the size of an Olympic swimming pool, I will construct a beach from multi-coloured sand. As waves disperse the sand, the resulting rainbow of sediment will reveal their pathways, which I will then quantify as a network in the digital laboratory. The resulting open datasets and numerical models will serve as a benchmark for the coastal research community, generating new theories and improved tools. My collaborators in the Netherlands, US, and New Zealand will help me to implement these findings in research, engineering practice, and coastal management policy. In this way I hope to enable more effective management of sediment for coastal adaptation and a more holistic understanding of our coastal systems.

Stay tuned for more updates once the project begins!