At TU Delft, a requirement for our PhD defense is to make ten propositions based on what we have learned during the previous years. Claims posed by my friends and colleagues deal with the nitty gritty details (“All diffusive processes can be derived from an advective one, and failing to do so yields incorrect modelling“[1]) but also the bigger picture of how we do what we do (“The way morphological models are presented and interpreted has a lot in common with predictions of snow depth in five years on December 26th at 4pm. The knowledge in these models deserves a better presentation“[2]).

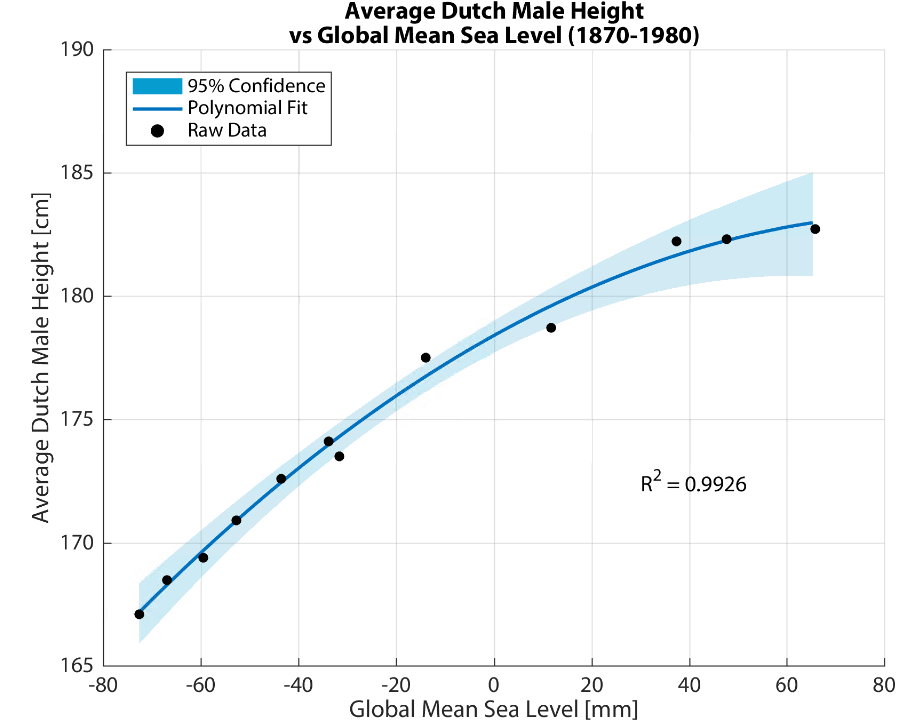

The propositions must be both defendable and opposable, so as to stimulate an interesting debate during the defense. Some of the propositions should reflect the findings of our research, but it is also traditional to include statements that have nothing to do with it. One colleague[3] even suggested (tongue in cheek) that the increase in the height of Dutch men over time could be explained by sea level rise. I couldn’t resist analyzing the data myself, and the results were surprisingly good:

These propositions are a chance to inject a bit of last-minute philosophizing into our Doctorates of Philosophy, and range from the wise (“No wind is favourable if a person does not know to what port (s)he is steering – Seneca“[4]) to the downright cheeky (“This proposition is not opposable“[1]).

What I Learned by Counting Sand for 5 Years

As the clock is ticking on my own PhD (259 days, 13 hours, 39 minutes, and 51 seconds, but who’s counting? *eye twitches*), I started preparing some propositions of my own (obviously in a fit of procrastination on my dissertation). After nearly five years of scrutinizing sand and contemplating connectivity, my research has led me to an inescapable conclusion:

Ebb-tidal deltas are badass morphological features (BAMFs),

(c.f. Phillips [2015]).

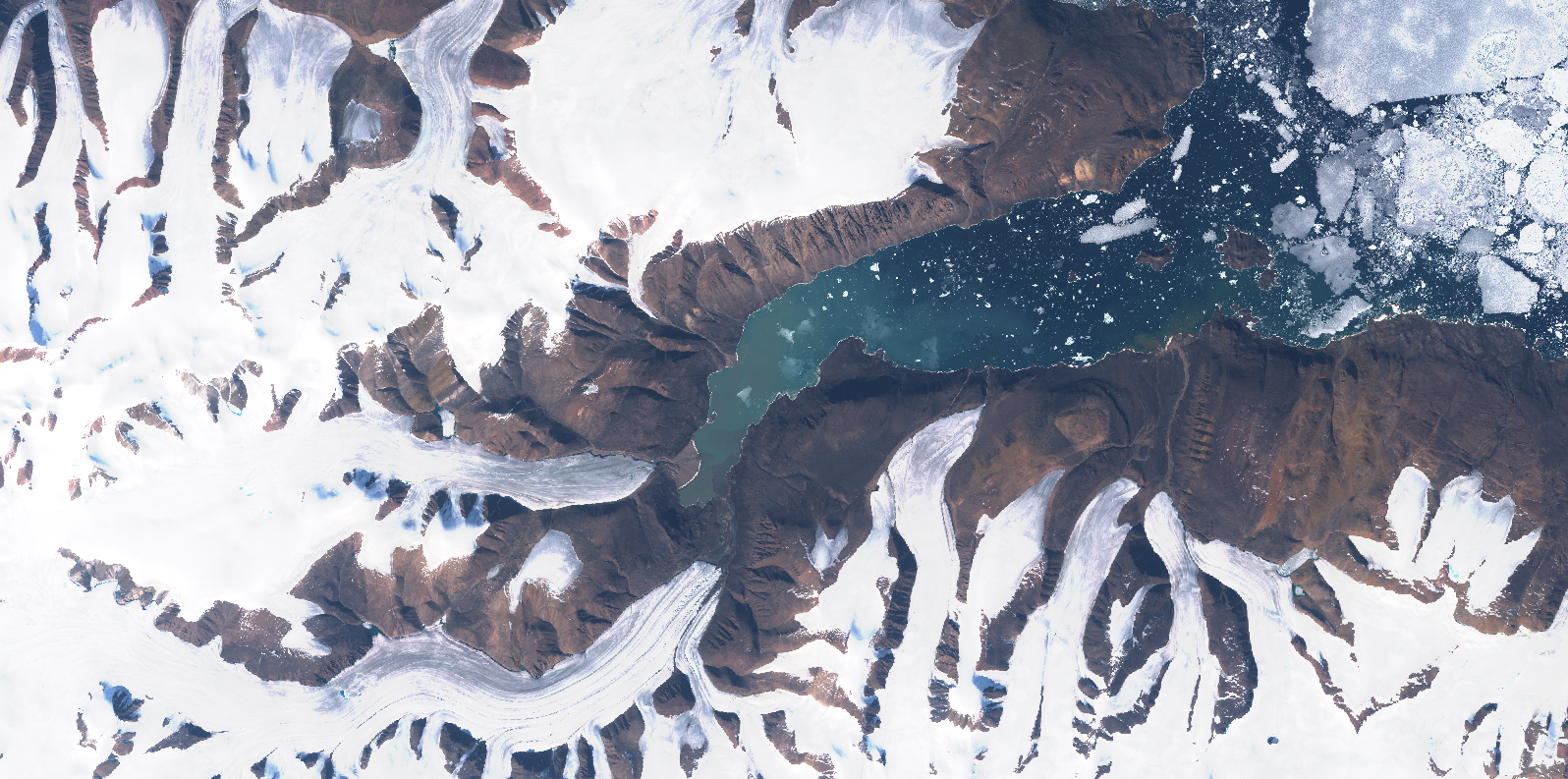

What, pray tell, is an ebb-tidal delta, and why is it so badass? Ebb-tidal deltas are large underwater piles of sand at the mouth of estuaries and tidal inlets, deposited by outflowing tides and reshaped by waves. I spend my days studying how waves and tides move sand around on the Ameland ebb-tidal delta in the northern part of the Netherlands (see below). We need to know this in order to plan ecologically-sustainable flood protection measures for the Dutch coast. A morphological feature is just a fancy name for some part of a landscape, like a hill or a valley or a beach.

What makes a badass “badass”?

Phillips[5] defines the archetypal badass as “individualistic, non-conformist, and able to produce disproportionate results”, and applies this concept to geomorphology (the study of how landscapes evolve, at the crossroads of geology and physical geography). Ebb-tidal deltas meet these three criteria, which makes them badass morphological features (BAMFs):

- Ebb-tidal deltas are each unique (in shape, location, composition, and in terms of the environmental forces shaping them (like waves and tides)), and hence individualistic.

- Ebb-tidal deltas are chaotic systems which defy accurate prediction using physics-based numerical models[6], and hence are non-conformist or “naughty”[7]. This numerical naughtiness is a serious problem for coastal engineers and scientists, since a failure to accurately predict ebb-tidal delta evolution can threaten public safety and lead to costly property or infrastructure damage. They do not “play by the rules” of our existing physics-based deterministic models.

- Ebb-tidal deltas are highly nonlinear systems which can greatly amplify small instabilities[8], and hence produce disproportionate results.

In addition to the strict definitions of Phillips[5], ebb-tidal deltas are also “belligerent or intimidating, ruthless, and tough”, other traits reflective of badassery [Oxford Engish Dictionary]. The Columbia River ebb-tidal delta alone is responsible for dozens shipwrecks in the past century, and Ameland ebb-tidal delta has also featured numerous wrecks throughout its history.

Quoting Thomas Pynchon[9], Phillips also notes that badasses are “able to work mischief on a large scale”. Ameland ebb-tidal delta covers an area of approximately 100 square kilometers, roughly the size of The Hague. Many ebb-tidal deltas around the world are even larger!

Seriously?

Now admittedly, ebb-tidal deltas are just big piles of sand. A big pile of sand is probably not the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word “badass”, unless you are Ralph Bagnold or a Sarlacc. This could probably also be considered gratuitous personification or anthropomorphization.

I’m sure that many of my friends and family have been scratching their heads as to why I would sacrifice the latter half of my 20s to understand them better. A critical reader might ask, “is it possible that you have only convinced yourself that ebb-tidal deltas are cool out of self-preservation?” And the answer is yes. Yes, I have. Nonetheless, I remain steadfast in my assertion that ebb-tidal deltas exhibit major symptoms of geomorphological badassery.

Although the concept of geomorphological badassery may seem silly at first, it illuminates several important truths of our (mis)understanding of these complex bathymetric features. Ebb-tidal deltas are important to study for reasons of coastal flood protection, navigational safety, and ecological value, but we are bad at predicting how they will evolve. This is because each ebb-tidal delta is unique, making it challenging to generalize their behavior. Furthermore, their chaotic, non-conformist behavior renders many of our usual deterministic prediction techniques ineffective. Lastly, the amplifying effect of highly nonlinear physical processes means that small physical changes (e.g., the development of a tiny shoal) could have disproportionately large consequences (e.g., relocation of a channel several kilometers wide). As such, badassery provides a useful conceptual framework for describing the challenges presented by ebb-tidal deltas to coastal engineers and scientists.

Badass.

References

[1] Chavarrias Borras, V. [2019]. Obtaining well-posedness in mathematical modelling of fluvial morphodynamics. PhD Thesis, Delft University of Technology.

[2] de Schipper, M.A. [2014]. Alongshore variability of nourished and natural beaches. PhD Dissertation, Delft University of Technology.

[3] Meirelles Nunes da Rocha, S. Effects of a stratified tidal flow on the morphodynamics. PhD Dissertation, Delft University of Technology.

[4] de Vet, P.L.M. [2020]. Intertidal Flats in Engineered Estuaries: On the Hydrodynamics, Morphodynamics, and Implications for Ecology and System Management. PhD Dissertation, Delft University of Technology.

[5] Phillips, J. D. (2015). Badass geomorphology. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 40(1), 22-33. (Yes, this is a legitimate scientific publication!)

[6] Elias, E., Teske, R., van der Spek, A., & Lazar, M. [2015]. Modelling tidal-inlet morphodynamics on medium time scales. In The Proceedings of the Coastal Sediments 2015.

[7] Kennedy, B. A. [1979]. A naughty world. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 550-558.

[8] Elias, E. P., Van der Spek, A. J., Pearson, S. G., & Cleveringa, J. [2019]. Understanding sediment bypassing processes through analysis of high-frequency observations of Ameland Inlet, the Netherlands. Marine Geology, 415, 105956.

[9] Pynchon T. [1984]. Is it O.K. to be a Luddite? The New York Times Book Review (October 28): 40–41.